The following is an exhibition review posted on the website of the International Journal of Comic Art. All copyright is theirs (or that of the respective authors). We are posting here for your information only. Thanks for their great work in the field of comic and cartooning studies.

Carrément Poilu. Sophie Baudry (curator). Brussels: Comics Art Museum, October 20, 2022 – August 15, 2023.

reviewed by Laurie Anne Agnese

Carrément Poilu (Squarely Furry), an exhibition celebrating Le Petit Poilu (Little Furry), is currently on view at the Comics Art Museum in Brussels. In 2007, the Belgian cartoonist Pierre Bailly and scriptwriter Céline Fraipont created the bande dessinée for preschool children; it has since expanded into an animated cartoon series and Dupuis will release the 28th album in March 2023. Le Petit Poilu’s world, his empathy and his penchant for humor also grows with each adventure and each album. Like the comic itself, this playful and interactive exhibition offers something for visitors of all ages but especially for fans of the comic.

The colorful entrance signals that this is a special comics exhibit – a small door welcomes just children under 5, and a larger one for everyone else.

There are no words, dialogue or narration in Le Petit Poilu. Children as young as three years old enjoy reading these wildly complex visual stories on their own. Since the albums can be read independently without their parents, Bailly and Fraipont speak directly to their youngest readers. “Wordless comics may have the strength to be able to speak to children as equals with a whole series of strategies to convey emotion, poetry, things like that” says Bailly in a video interview playing at the exhibit (translation from French is mine).

Le Petit Poilu balances simple and fun adventure stories with serious themes such as migration, gender or playground aggression. Bailly and Fraipont put immense care into the sequencing of the story and ultimately a great deal of trust in children: “We offer them an opportunity to go very far in their capacities, in their intelligence to be able to decipher a story, even at 3 years old. I think it makes children, as soon as they bite, want to taste it again.”

Once in the exhibit hall, children immediately notice the free maps of the exhibit and without words or instructions, they also know exactly what to do with them. The maps showed the layout and also gave them a mission at each stop: find the colored stamps to complete the map. The map is also self-referent to the series. It is a souvenir to take, like Petit Poilu, who always returns home with a special object from his adventures.

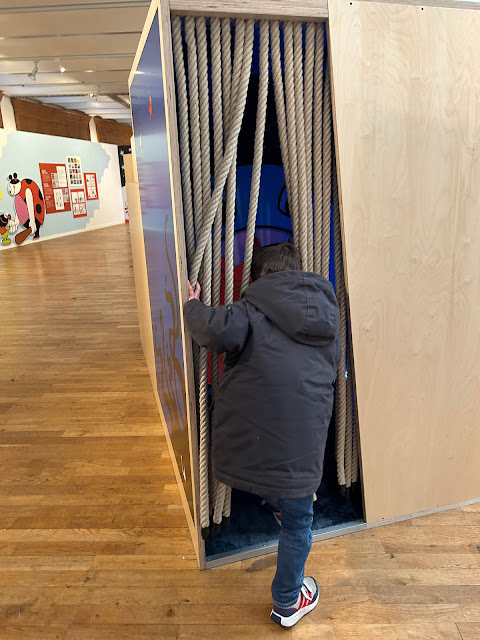

There are several large enclosed wooden cubes with small entrances that invite visitors to get low to the ground and discover what is inside. There was a note to give priority to the youngest visitors, but families tended to explore the cubes together. So the young and the old climbed, jumped, hid and crawled through each of them and immersed themselves in these unique worlds that reference particular stories in the series.

Each album of Le Petit Poilu follows a similar structure with endless variety, like the daily life of a preschool child. Poilu wakes up, uses a toilet that is too big for him, eats breakfast, says goodbye to his parents and walks to school. But then something strange and magnificent happens. He discovers a new universe and an unexpected adventure awaits him. The cubes capture this magical turning point: bright, vivid images from the bande dessinée combined with the sensory experiences of music and textures to depict this triggering event that puts the story into motion.

For example, the cube for La Sirène Gourmande (the first album in the series) is an underwater story where a large hungry mermaid swallows Le Petit Poilu, and he lands in a pile of rubbish that is her belly where the adventure to get out takes place. The cube is awash in the beautiful underwater imagery and sounds, and the belly of trash is soft.

One very small cube discreetly sits in an unremarkable corner, and could be mistaken for a mouse hole. Once down on the ground, the visitor sees that it depicts the adventures in Madame Miniscule, where the size is turned upside down, and Le Petit Poilu as the child is large, and the adults and all of the objects around them are very small in comparison.

Because of its clever use of structure and repetition, Le Petit Poilu has a musical and rhythmic quality. Each story hits similar moments with visual cues: Poilu shakes hands with a friendly character who will help him in the conflict; he looks longingly at a photo of his mother to give him courage to face the mounting adversity, and when the problem has resolved itself, he receives a special object to take home. All 27 objects from his 27 adventures are collected in a special cabinet adorned overhead with his clown nose:

Like Alice in Wonderland and The Phantom Tollbooth, Le Petit Poilu is ultimately a voyage and return adventure story. Once he receives the special object, the story ends by unspooling itself: Poilu returns home, reunites with his parents, eats dinner, and goes to bed. All alone in his room, he checks his bag and finds the object that he received – proof that the magical adventure took place – and brings both his world and the magical one together.

Lining the perimeter of the hall, large reproductions from the albums, sketches, original artwork and descriptive panels invite parents and children to learn together about the creation and backstory of the comic. These panels are kept simple and placed at sight level to interest the younger visitors, but in reality, I did not see many children looking at them. They explained the process of creating a wordless comic, which starts with words and storyboarding first. Other panels highlighted the process of creating the look of Le Petit Poilu from a drop of ink.

The exhibit ends with two adjacent rooms – one is furnished with a soft rug, floor cushions, and low bookshelves with multiple sets of the entire series available to read; the other features a television screen. Many visitors lingered there for nearly an hour. It is a unique opportunity to read all 27 albums in one uninterrupted sweep, and visitors approached it in their own way. Some parents sat down on the floor and read the books to their children – that is, the parent created and narrated a story out loud from the pictures. Some children and parents were side by side reading silently to themselves.

The other room features a looped video interview with Bailly and Fraipont. The bench for watching is full-sized, and is surrounded by small sketches hung high. In the video, the sound is off, and the subtitles are on – squarely aiming this space for the adults, perhaps to distract them long enough to leave the children alone to read the books.

In the video interview, Bailly remarks how sometimes “words freeze and block things.” Drawing on a parallel with the silent films of Charlie Chaplin or Buster Keaton, he adds “there is not only burlesque, there are also a lot of emotions and humanity. This kind of intimacy with character is something that we can understand and feel without words.” In the albums, as well as the exhibit, there is space for fantasy within the reader and for their own words to tell the story.

All photos taken by Laurie Anne Agnese unless otherwise noted.